Context-based steering

Problem

You need an AI-controlled object in your game that can follow a path, avoid obstacles, and make other decisions about how to move around the world.

Solution

“Steering behavior” is the blanket term for a variety of algorithms that you can use to solve this problem. Which one you choose will depend on your game, the type of world the object lives in, and what type of “intelligence” you want it to have.

In this example, we’re going to use a method called “Context Behavior”, which aims to give the object enough information about the world to make a choice of how to move. For additional reading on this subject, see the following links:

For this demo, we’ll use a generic “Agent” object. In your game, this might be a car driving around a track, a monster patrolling a dungeon, or some other kind of game entity. Our agent will use a KinematicBody2D, but remember, you can use this technique with any kind of object - the algorithm is about the entity choosing a direction to move, how it moves is entirely separate.

The Algorithm

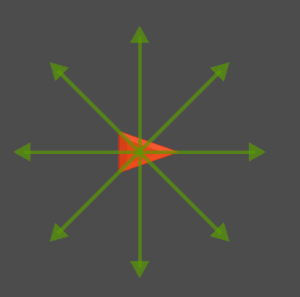

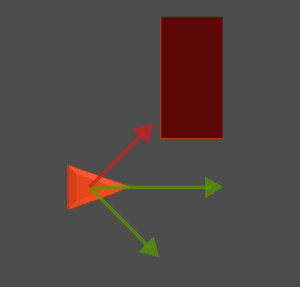

To begin, let’s imagine our agent has a number of rays extending in all directions (we’ll talk about how many to use later - for now let’s use 8).

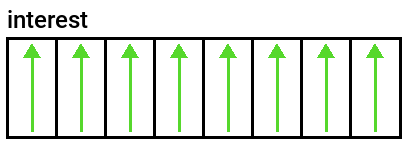

In our agent’s script, we’ll store an array called interest, tracking in which directions the agent wants to go.

Of course, if they’re all the same, then it can’t move - it wants to go in all directions equally! So lets consider that it has a preference - it mostly wants to go forward:

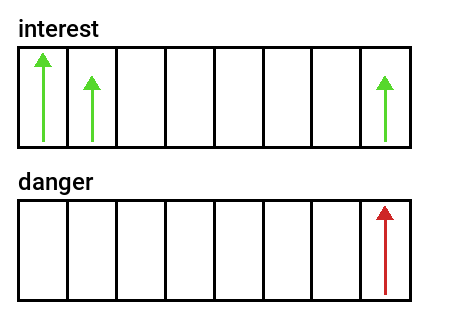

In this case, the interest array would look like this:

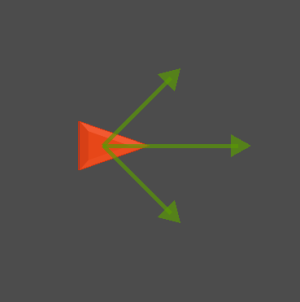

The strongest desire is to go forward, but forward-left and forward-right are acceptible as well. But what if an obstacle appears?

Now we’ll introduce a second array, danger, that indicates directions that are not preferred.

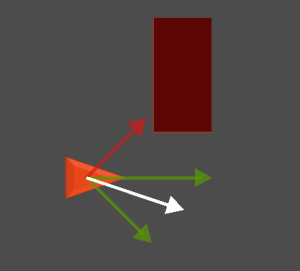

Combining these two arrays, we can eliminate any interest directions that are also contained in danger. By summing up the remaining interest directions, we’re left with a new direction pointing away from the obstacle.

To summarize:

- Find the object’s

interestdirections. - Find the directions that contain

danger. - Eliminate any

interestdirections that are dangerous. - Sum the remaining

interestdirections to find the new heading.

Finding Interest

This will vary depending on what your agent’s goal is. If it’s to chase the player, then the interest values should be high in the direction of the player. You can even have multiple targets: closer goals have higher interest, but if an obstacle cancels them out, the lower scoring goals will win.

For this demo, we’re going to imagine we’re making a racing game of some kind. The AI-controlled cars need to make it around the track: their interest array should be pointing forward along the track, so they don’t start going backwards.

There are a few ways to do this, and in order to keep our agents from needing to know the implementation details, we’ll have the track tell them which way to go based on their position. At any time if you ask the track which way is correct, it will tell you.

The Code

Here’s the code for our agent. We start with the exported values: movement parameters and other values we want to be able to adjust easily. look_ahead, for example, is how far ahead the danger rays will detect obstacles.

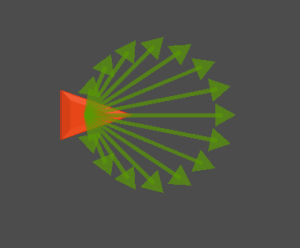

Note that we’ve made the num_rays adjustable, so that you can find the number that works best for your situation. We’ll talk below about the tradeoffs and benefits of larger numbers of rays.

extends KinematicBody2D

export var max_speed = 350

export var steer_force = 0.1

export var look_ahead = 100

export var num_rays = 8

# context array

var ray_directions = []

var interest = []

var danger = []

var chosen_dir = Vector2.ZERO

var velocity = Vector2.ZERO

var acceleration = Vector2.ZERO

Next, we have _ready() where we size the arrays properly and populate the ray_directions array with the actual ray vectors, distributing them evenly around the circle based on num_rays. We begin with no rotation, so Vector2.RIGHT is forward.

func _ready():

interest.resize(num_rays)

danger.resize(num_rays)

ray_directions.resize(num_rays)

for i in num_rays:

var angle = i * 2 * PI / num_rays

ray_directions[i] = Vector2.RIGHT.rotated(angle)

In _physics_process() we’ll populate the context arrays and execute the movement. Note we’ve broken the steps of the algorithm in to separate functions. Once we’ve found our chosen direction, we turn towards it as much as possible (based on steer_force) and move.

func _physics_process(delta):

set_interest()

set_danger()

choose_direction()

var desired_velocity = chosen_dir.rotated(rotation) * max_speed

velocity = velocity.linear_interpolate(desired_velocity, steer_force)

rotation = velocity.angle()

move_and_collide(velocity * delta)

Now we’ll go over the 3 functions that make up the algorithm. first, setting the interest array. As mentioned above, we’re going to ask the world (our owner in this case) to tell us which direction we should be trying to go.

Using each ray direction, we take the dot product with the given path direction. Recall that the dot product of two aligned vectors is 1 and for two perpendicular vectors it’s 0. We ignore negative values - 0 means we don’t want to go that way.

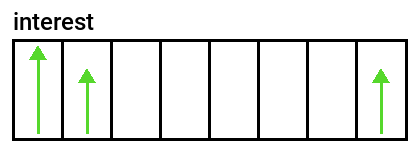

For example, with 32 rays, the interest would look like this:

As a safety measure, if there’s no owner to tell us a direction, we’ll default to trying to go forward.

func set_interest():

# Set interest in each slot based on world direction

if owner and owner.has_method("get_path_direction"):

var path_direction = owner.get_path_direction(position)

for i in num_rays:

var d = ray_directions[i].rotated(rotation).dot(path_direction)

interest[i] = max(0, d)

# If no world path, use default interest

else:

set_default_interest()

func set_default_interest():

# Default to moving forward

for i in num_rays:

var d = ray_directions[i].rotated(rotation).dot(transform.x)

interest[i] = max(0, d)

Now we can populate the danger array. Using the Physics2DDirectSpaceState, we cast a ray in each direction. If there’s a hit, we add a 1 in that spot.

func set_danger():

# Cast rays to find danger directions

var space_state = get_world_2d().direct_space_state

for i in num_rays:

var result = space_state.intersect_ray(position,

position + ray_directions[i].rotated(rotation) * look_ahead,

[self])

danger[i] = 1.0 if result else 0.0

Finally, we can use the context arrays to choose our direction. Looping through the danger array, zero the interest wherever there’s danger. Then, sum up and normalize the remaining interest vectors.

func choose_direction():

# Eliminate interest in slots with danger

for i in num_rays:

if danger[i] > 0.0:

interest[i] = 0.0

# Choose direction based on remaining interest

chosen_dir = Vector2.ZERO

for i in num_rays:

chosen_dir += ray_directions[i] * interest[i]

chosen_dir = chosen_dir.normalized()

Example in Practice

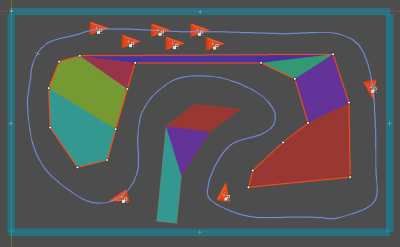

Let’s try it out in action! Here, we’ve created a track using a Path2D and some collision polygons.

In the script for this scene, we have a get_path_direction() function. Given a position, this function finds the closest point on the path and puts the PathFollow2D there in order to find the forward direction.

func get_path_direction(pos):

var offset = path.curve.get_closest_offset(pos)

path_follow.offset = offset

return path_follow.transform.x

We’ve randomized the speeds of the agents do get some variety. Notice how the fast one finds ways to dodge around the slow ones.

Wrapping up

This method is very flexible and can be extended to produce a wide variety of complex-looking behaviors. It

Here are some additional suggestions for adaptations/improvements:

- Levels of danger

When populating the danger array, don’t just use 0 or 1, but instead calculate a danger “score” based on the distance of the object. Then subtract that amount from the interest rather than removing it. Far away objects will have a small impact while close ones will have more.

- Avoidance

Rather than a danger item canceling the interest, it could add to the interest in the opposite direction.